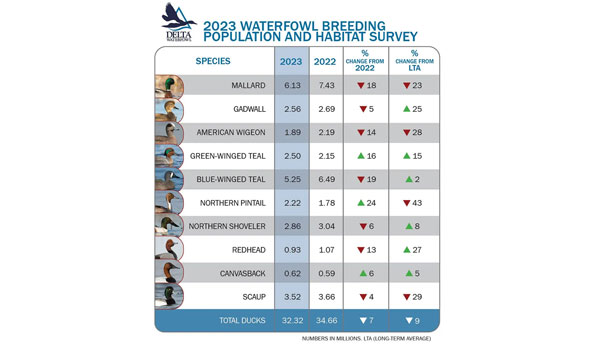

The breeding population of ducks declined 7-percent this spring, while pond counts dropped by 9-percent compared to last year, according to the 2023 Waterfowl Population Status report released Friday by U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS).

Those numbers resulted from the Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey, which has been conducted annually by the USFWS and Canadian Wildlife Service since 1955, except for 2020 and 2021 because of COVID-19 concerns. The survey, which is used to set hunting regulations throughout North America, estimated a breeding duck population of 32.3 million ducks in the traditional survey area, which is 7-percent less than 2022 and 9-percent below the long-term average. Importantly, the May pond count, a key indicator of duck habitat and potential production, showed 4.98 million ponds, a 9-percent decrease and 5-percent below the long-term average.

The numbers might seem discouraging on the surface, but Dr. Frank Rohwer, president and chief scientist of Delta Waterfowl puts forth an important reminder: “We don’t hunt the breeding population. We hunt the fall flight, which is made of the breeding population plus this year’s duck production. Duck production is the key to the upcoming hunting season.”

Rohwer and other waterfowl managers see plenty of reasons for optimism. Timely rains after the survey was conducted should boost duck production in key areas of the prairie pothole region, including the Dakotas and southern Saskatchewan.

“I think duck production is going to be a much better picture than what we’re seeing in these survey numbers,” Rohwer said. “The Dakotas got rain in late May after the pond count data was assessed, and then we’ve had intermittent rain throughout the summer. Many areas of the key PPR breeding grounds stayed relatively wet, and that’s really good for re-nesting and duckling survival—two of the big drivers of duck production. Saskatchewan started the spring with better water conditions than in 2022, and summer rains helped keep that water later in the nesting season than we have seen in recent years. I was impressed by the number of blue-winged teal broods I saw in southern Saskatchewan in July.”

While water is the key driver of duck nesting and re-nesting effort, predation is the key determinant of whether duck eggs hatch or fail. According to Mike Buxton, waterfowl programs director for Delta Waterfowl, the extreme winter that socked the Dakotas and southern Manitoba helped knock back the populations of duck-nest predators such as raccoons and skunks. Buxton runs Delta’s Predator Management Program.

“The Dakotas got a lot of snow in early November, and winter never let up until mid-April,” Buxton said. “We never had that winter thaw. It was a long, hard, cold winter. Any animal that wasn’t in tip-top shape going into the winter probably had it rough.”

Fewer predators on the landscape always helps nest success, and in turn, duck production.

Looking at breeding survey estimates for individual species, mallards came in at 6.1 million in the traditional survey area, an 18-percent drop from last year. The estimate puts mallards 23-percent below the long-term average—the lowest index since 1993. Regionally, mallard numbers declined by 36-percent in the eastern Dakotas and 50-percent in southern Saskatchewan, while increasing 8-percent in southern Alberta.

Blue-winged teal, the second most abundant duck in North America, declined a shocking 19-percent from last year. At 5.25 million, bluewings are still -percent above the species’ long-term average. The eastern Dakotas, which were exceptionally wet in 2022, still had fairly good spring water this year. According to the survey, the region attracted just over 2-million breeding bluewings, which is down a whopping 39-percent from the previous year.

“Bluewings are the big surprise for me,” Rohwer said. “I thought they had pretty good production last year in the prairies, especially in the eastern Dakotas, yet the number went down. This spring, some of those teal kept going past the 49th parallel and settled in southern Saskatchewan, where their numbers jumped by 16-percent this year. However, the total breeding population dropped more than I would have predicted.”

Pintails, a favorite duck for many, bounced back nicely from a record low in 2022. The pintail estimate is 2.22 million, up 24-percent year over year, but still a troubling 43-percent below the long-term average. Of interest, pintail numbers jumped 54-percent in the eastern Dakotas, 203-percent in southern Saskatchewan, and 126-percent in southern Alberta.

“Pintails made a big improvement,” Rohwer said. “They’re an early nesting species. The pintails arrived in the Dakotas right when the huge winter snows melted, so they settled in to take advantage of the good early water conditions.”

Green-winged teal breeding populations also climbed. Greenwings are estimated at 2.5 million, up 16-percent from last year and 15-percent above the long-term average. Greenwings nest predominately in boreal forest regions such as northern Alberta, British Columbia, and the Northwest Territories.

Among other puddle ducks in the survey, gadwalls declined 5-percent but remain a healthy 25-percent above the long-term average. Similarly, shovelers declined 6-percent but stand 8-percent above the long-term average. Wigeon are not doing as well—they dropped 14-percent and sit 28-percent below the long-term average.

Dr. Chris Nicolai, who oversees Delta’s research program, said production from prairie nesting puddle ducks—particularly blue-winged teal, gadwalls, and shovelers—appears to be good to excellent across the Dakotas and eastern prairie Canada.

“My observation from field work and driving around is that duck production was really good in the Dakotas,” Nicolai said. “I’ve been seeing broods of puddle ducks all over.”

Results are mixed for diving ducks. Canvasbacks increased to 619,000, up 6-percent and 5-percent above the long-term average. Redheads declined to 931,000, down 13-percent but still 27 above the long-term average. Scaup continued to trend downward, dropping 4-percent in 2023, which puts them 29-percent below the long-term average.

Duck numbers in the eastern survey area—birds most likely to migrate down the Atlantic Flyway—are strong. Although mallards declined 4-percent, they held above 1.2 million, which should keep a four-mallard daily limit in place for the 2024-2025 season. Black ducks, at 732,000, rose 8-percent and are now 6-percent above the long-term average. Green-winged teal increased by 17-percent, while goldeneyes were up 28-percent. Ring-necked ducks declined by 3-percent and mergansers fell by 1-percent. Populations of wood ducks, one of the species in the formula used to determine season lengths and bag limits in the east, held steady at a robust 1 million in the Atlantic Flyway.

Overall, this year’s duck production—and hunting during the upcoming season—is likely to be a mixed bag.

The Waterfowl Breeding Population and Habitat Survey data is released in late August—months after the actual counting because it is a massive effort to survey the continent’s waterfowl. Ironically, the survey is simply a snapshot of the breeding population and habitat in early spring. Although the breeding population numbers are slightly below average, remember that production in the summer has far more to do with fall hunting success than a snapshot of pair numbers.

“I think production this summer was far better than what pair numbers would suggest,” Rohwer said. “We had very timely rains in much of the PPR and water stayed on the landscape. Couple that with reduced predator numbers, and it is a recipe for success. I’ve seen teal broods everywhere across the prairie, and young mallards dominate the ducks caught during banding efforts in Manitoba. That makes me very excited about the upcoming hunting seasons.”

A humble homesteader based in an undisclosed location, Lars Drecker splits his time between tending his little slice of self-sustaining heaven, and bothering his neighbors to do his work for him. This is mainly the fault of a debilitating predilection for fishing, hunting, camping and all other things outdoors. When not engaged in any of the above activities, you can normally find him broken down on the side of the road, in some piece of junk he just “fixed-up.”